by emilie.cremin@gmail.com | Nov 27, 2025 | Blog, Previous Events, Upcoming Events

ENGAGE4 Sundarbans receives LIVING WITH RIVERS LABEL

“A Label that speaks of possibilities and shares enthusiasm!”

Erik Orsenna, IGFR President

In line with the first international action, Living with Rivers 2022, IFGR is continuing to promote actions in the field for the Future of Rivers!

In 2024, IFGR is setting up with its expert committee the first International River Initiatives Label.

This label aims to highlight positive initiatives and tell of the commitment of actors rooted in the territories in response to the significant challenges facing rivers. Reference indicators established by the IFGR expert committee are used to select initiatives in France and abroad, within a systemic and multidisciplinary framework that takes into account uses.

Find all the labelled initiatives: https://www.initiativesrivers.org/le-label-living-with-rivers/labeled-initiatives/

ENGAGE4Sundarbans page

This multidisciplinary approach opens the selection to an extensive range of initiatives whose expected goals and impacts should strengthen the sustainability of rivers, their territories and their populations.

We intend to provide support to the contributors of initiatives as closely as possible to their needs and to facilitate their actions (financial prizes for the 3 winners, contributions of expertise and visibility, networking, etc.).

We are convinced that it is by action in the field that we can make an impact collectively and inspire other actors. Therefore, we want to place ourselves in the service of those who act concretely in the territories.

Our intention is to provide support to the contributors of initiatives as close as possible to their needs, and facilitate their actions (financial prizes for the 3 winners, the contribution of expertise and visibility, networking, etc.).

We are convinced that it is by action in the field that we can make an impact collectively and inspire other actors. Therefore, we want to place ourselves in the service of those who act concretely in the territories.

by Spriha Roy | Oct 13, 2025 | Blog, Inland Fisheries

Of Fish and Futures: A Grand Beginning through Re/lease

Blog by Spriha Roy, IIT Kharagpur. Spriha.roy24@gmail.com

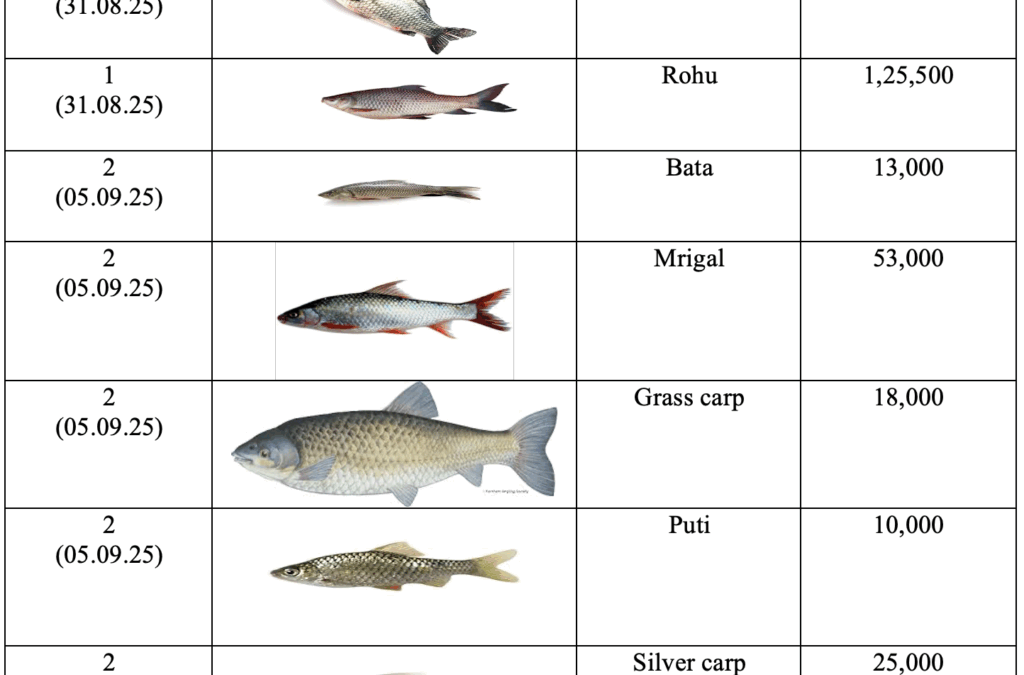

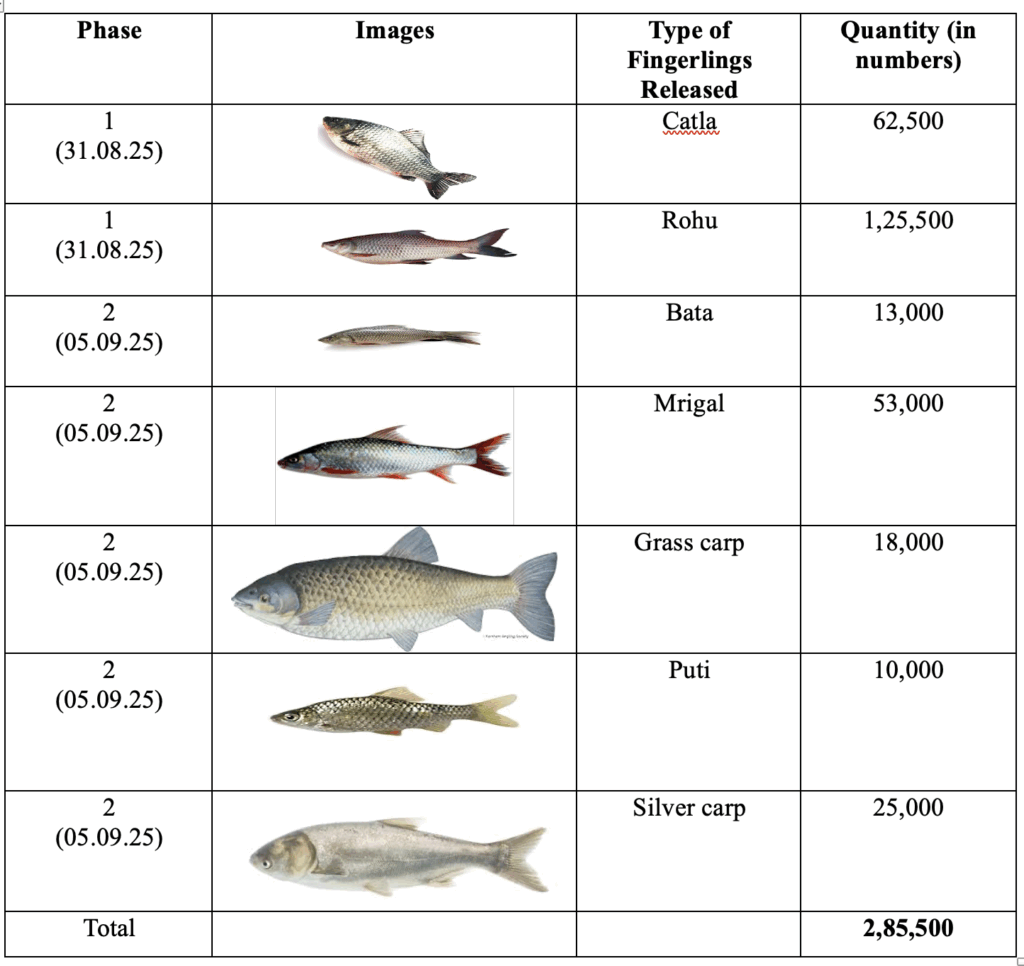

On the 31st of August and the 5th of September 2025, the Mukherjee Canal in Kumirmari, an island situated in Gosaba block of the Indian Sundarbans, came alive with a vibrant community activity that focussed on ecological renewal. Spearheaded by the Sarsa Group—a collective comprising 41 households residing along the canal, the activity signified a milestone in the ongoing Collectivised Canal Fishing Experimentation (CCFE) initiative under the ENGAGE4Sundarbans project.

This two-phase release of fish fingerlings, conducted under the guidance of a transdisciplinary Indian team comprising academic researchers, local field implementation partners, advisory committee members, and technical experts from the Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFRI), brought together diverse forms of knowledge—scientific, traditional, and shared. As the fingerlings were gently introduced into the canal, the act of re/leasing became both a material and a symbolic gesture: of reinhabiting ecologies, of reimagining collective futures, and of reaffirming community-led management over shared aquatic commons.

This photo essay attempts to document not only the technical interventions in collectivised inland fishing, but also tries to highlight the deeply embodied place-based nuances of inter-generational knowledge systems, sustainable practices and hope. The images capture the multi-sensory textures of the occasion: the muddy feet and monsoon skies, the choreography of coordinated human chain carrying the boxes to the rhythms of dhak and conch shells, and systematically releasing the fingerlings to the canal.

Behind the Scenes of Planning and Logistics

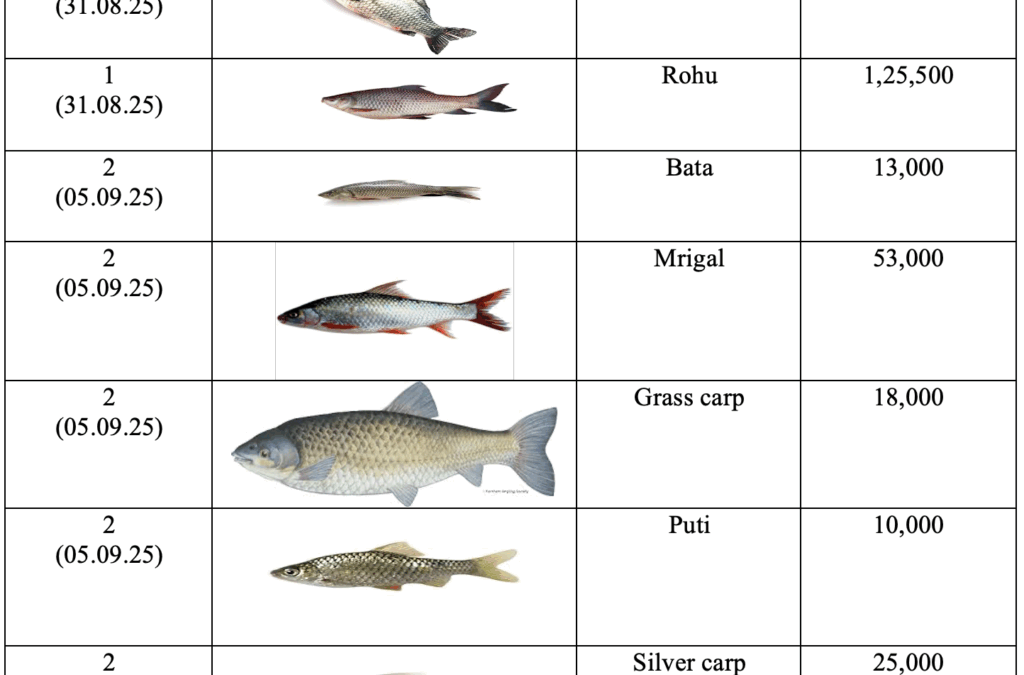

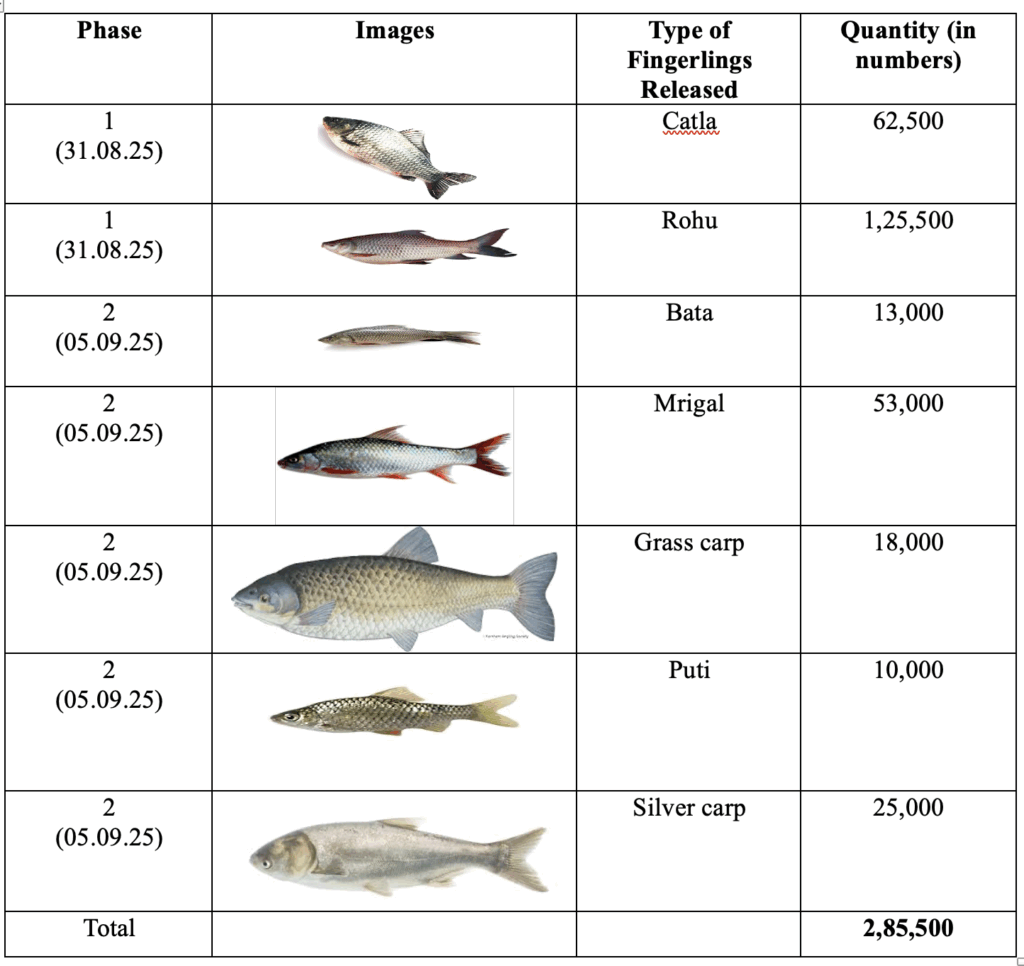

The fingerling release was preceded by intensive planning involving the project team, local community members, and technical experts. Multiple consultations were held to determine ecologically appropriate methods for releasing during both phases of the activity. Fingerlings were procured from a certified vendor in Naihati, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, and was transported in oxygenated plastic bags. The consignment included approximately 285,500 fingerlings distributed across seven species:

Each fingerling measured between 0.75-0.90 inches and weighed about 0.3 grams. The operation was coordinated under the supervision of a CIFRI principal scientist, in collaboration with the IIT Kharagpur team. After reaching Dhamakhali, the consignment was transferred to a boat and transported to Sucharita Sangha Ghat (Bonbibi Tala) in Kumirmari, the nearest access point to the Mukherjee Canal.

Image 1. Boat loaded with boxes of fingerlings brought to Sucharita Sangha Ghat in Kumirmari.

Image 2. Sarsa members welcoming the boat with great enthusiasm!

Rituals of Invocation

As the consignment of fingerlings reached Sucharita Sangha Ghat, the community gathered to celebrate this moment with traditional ritual of Makal and Ganga puja. Accompanied by the rhythmic beat of dhaks (traditional drums) and echoing vibrations of ullu and conch shells, members of the Sarsa Group offered prayers to invoke the blessings of the river. This act of reverence emphasises the culturally embedded symbolism of water in the community—as both a life-sustaining presence and a sacred force. Such traditional interventions serve as a medium between the perceived scientific practice and the unseen beliefs.

Image 3. Community members performing traditional rituals before the fish release.

Image 4. A member of the Sarsa group performing Ganga Puja.

Image 5. A collective comprising intergenerational participation and a commitment to sustaining the canal as a community-managed resource.

Collective Mobilisation through Human Chain

Following the offering rituals, community members formed a human chain to transport oxygenated boxes of fingerlings from the ghat to the canal’s edge. Navigating muddy terrain and narrow paths, this coordinated effort reflected both logistical precision and a shared sense of responsibility. The act of carrying became more than a practical task as it reflected collective effort in sustaining their canal ecosystem.

Image 6. Members of the Sarsa group carrying fingerling boxes from the ghat to the canal through a coordinated human chain.

Image 7. The members are walking across the Mukherjee canal with the boxes.

Image 8. Stacking the boxes at the end of the canal before the release.

Fingerlings Releasing Protocol

The release process followed standardised acclimatisation protocols to minimise stress and improve post-release survival. As per guidance from Dr. Archan Kumar Das, Principal Scientist at CIFRI, the oxygenated plastic bags, also referred to as fingerling balloons—were placed on the surface of the canal water, allowing them to float for approximately 15 minutes to achieve thermal equilibrium.

To further reduce stress on the sensitive fingerlings, about 100 ml of canal water (roughly one mug) was carefully added to each bag to initiate gradual acclimatisation. Once the fingerlings exhibited active movement, they were gently released at the canal’s edge, minimising shock and dispersal stress. This carefully managed process reflects a synthesis of technical precision and ecological care, integral to the broader aims of the Collectivised Canal Fishing Experimentation (CCFE).

Image 9. Floating fingerling balloons.

Image 10. Gradually adding 100ml canal water to each of the fingerling balloon.

Image 11. Releasing fish fingerlings in the canal.

More than the Re/lease: Reflections on Practice, People and Place

While the activity unfolded and began to gather momentum, an elderly man stood at a distance, observing the process attentively. When approached, he shared, “Though I am not a member of this collective, I am aware of the community initiative taking place, and I feel happy for my neighbours. My son works as a migrant labourer, and I run a small shop near the ghat. My earnings are sufficient, and I am able to manage. But this activity will help others to find ways for living.” His words mirrored not only a sense of solidarity, but also an acute awareness of the broader socio-economic impact this experiment promises to offer.

Among the Sarsa team members, one elderly participant stood out for his remarkable energy and commitment. Despite his age, he actively assisted in unwrapping the boxes with a level of stamina comparable to that of younger volunteers. When asked about his age, he responded, “I am 70 years old, and the first house in this lane belongs to me. Since my son is currently away for work, I am here to take his place. I may not be equipped to carry out the more complex procedures, but I can certainly help with unboxing the cardboard packages.” Such reflections are deeply meaningful in understanding the fundamental idea that no contribution is insignificant. His involvement, though modest in scope, played a vital role in supporting the overall coordination and success of fingerlings release event, highlighting the importance of inclusive community participation across generations.

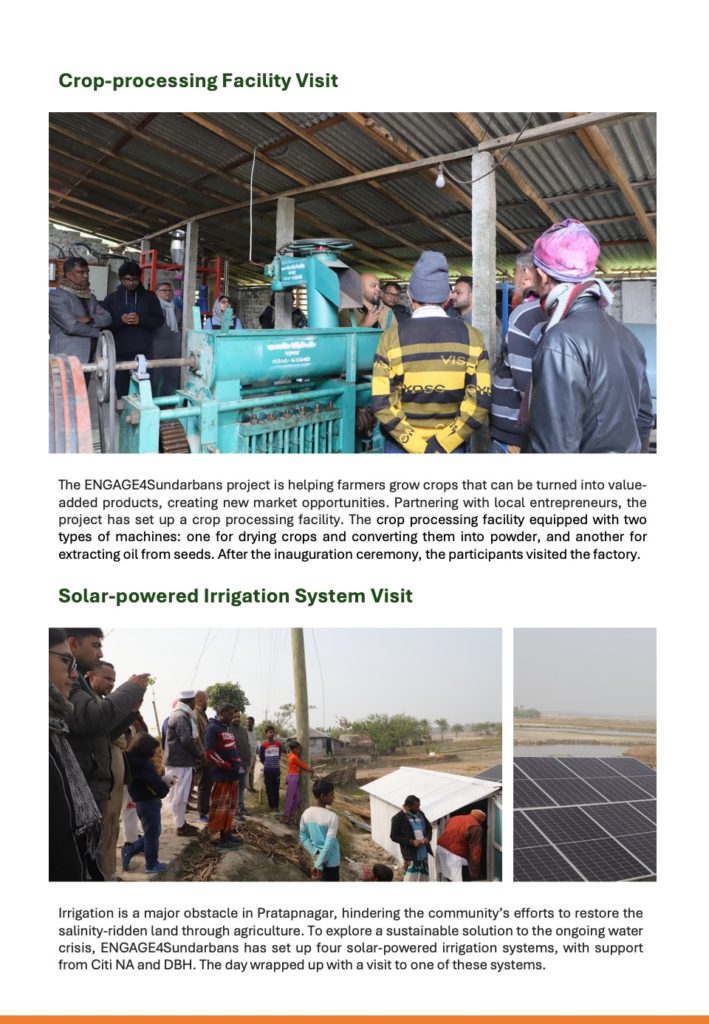

by Shimim Mushsharat | Jul 8, 2025 | Blog, Resources

Rahima Khatun’s life has been shaped by challenges. She lives with her husband, one of her sons, his wife, and their child. Her two other sons have married and moved out. Her husband, now elderly, is unable to work much, and the son who lives with them is only able to earn seasonally. Together, their incomes are not enough to support the family of five.

With no land in their name, they faced not just financial uncertainty but also a lack of food security.

But Rahima is not one to be intimidated by obstacles. Through sheer determination and persistence, she turned her hardship into an opportunity.

Rahima Khatun grows a multitude of vegetables on her yard.

A Natural Leader in the Field

When SAJIDA Foundation’s ENGAGE4Sundarbans project started its ethnographic research, Rahima was selected as research participant due to her involvement with agriculture. She spoke candidly during interviews, sharing her farming knowledge and the struggles that came with having limited land and financial resources.

From the beginning, Rahima was determined to carve out a space for herself in her family and community. She was surprised and encouraged when she learned she had been selected to join one of ENGAGE4Sundarbans’s intervention groups testing crops with high value addition potential. She was placed in the group assigned to grow fennel along with two other female farmers.

Before long, Rahima became much more than just a participant. She took the lead in group planning, organised meetings, and became an active figure in project activities. Even her husband began to support her involvement, gradually letting go of his initial doubts.

As part of ENGAGE4Sundarban project’s group farming initiative, she now cultivates rice, grains, and vegetables on the land next to her home. In another small plot of just two decimals, she farms freshwater fish for her family’s consumption. Her yard, too, has a multitude of vegetables growing. Years ago, her elder son started building a roofed house, but financial constraints postponed the construction. Rahima, ever resourceful, transformed the unfinished structure into yet another thriving vegetable garden.

Through determination and persistence, Rahima has turned her hardship into an opportunity.

A Home Garden to Ensure Food Security

What truly sets Rahima’s farming apart is her commitment to diversity. During the monsoon, she grows Aman paddy. Once harvested, she uses the same land to plant potatoes, sunflowers, fennel, sesame, and melon during the Rabi season from Mid-November to Mid-March. In other plots, she cultivates mustard alongside red cabbage, spinach, radish, and coriander, aubergine, onions, beans, beetroot, gourd, and winter crops like spring onions, garlic, and chillies also find space in her garden. Her motivation is both practical and personal. She refuses to buy oil or vegetables from the market.

“Why spend money [on oil or vegetables] when I can grow them myself?” Rahima, a traditional farmer and participant of ENGAGE4Sundarbans project, says.

One of Rahima’s long-held dreams was to lease land in her own name, so she could grow rice without depending on others. Her wish came true when ENGAGE4Sundarbans leased land under the names of Rahima and her group members.

Looking ahead, Rahima hopes that by selling fennel in the Rabi season and vegetables during Kharif (Mid-March to Mid-November), she can earn enough to lease more land and commercially scale up her farming.

by Shimim Mushsharat | Jun 26, 2025 | Blog, Previous Events, Uncategorized

Jayanti Rani Saha lives in Pratapnagar, Assasuni, one of the climate change hotspots in Bangladesh. She is a housewife, sharing a modest home with her husband and three daughters. Her husband earns just enough to sustain their family of five. But Jayanti’s determination to contribute has turned their yard into a thriving oasis of hope and sustainability.

Jayanti is a proud member of a female farmer group supported by SAJIDA Foundation’s ENGAGE4Sundarbans project. This project aims to strengthen social and climate resilience in the Sundarbans delta, an area heavily affected by climate change. Together with her groupmates, Jayanti is currently cultivating beetroot to produce beetroot powder, which contains both nutritional and economic value.

Although Jayanti’s family doesn’t own agricultural land, they have two small ponds where they farm freshwater fish. But Jayanti’s transformation is most visible in her kitchen garden. She nurtures the garden with advice and training from SAJIDA Foundation. Determined to cultivate a healthy and self-sustaining lifestyle, Jayanti has transformed her garden into a diverse ecosystem.

In the winter, she focused on cultivating eggplants along with other vegetables. She crafts natural fertilisers and pesticides from kitchen leftovers, cow dung, and poultry manure instead of using chemicals in her garden. Her reasoning is simple yet profound, “Chemicals harm the insects and animals that are valuable for the environment. And I want my children to eat healthy food.” Her commitment to agroecology is a testament to her intuitive understanding of sustainable living.

“Chemicals harm the insects and animals that are valuable for the environment. And I want my children to eat healthy food.”

— Jayanti Rani Saha, Member of a female farmer group under ENGAGE4Sundarbans Project

Beyond cultivation, Jayanti repurposes household waste into fertiliser, pesticide, and cooking fuel. Cow dung cakes, neatly arranged on a coconut tree trunk in her yard, dry in the sun before being used as eco-friendly fuel. Her forward-thinking approach includes designating one eggplant plant as a seed plant, ensuring her family’s self-reliance in the next planting season. Notably, Jayanti’s garden also blooms with a vibrant scattering of flowers that attract beneficial insects, helps with pollination and also makes the space beautiful.

The backdrop to Jayanti’s story is Pratapnagar’s slow recovery from Cyclone Amphan, which devastated the region in 2020. The cyclone triggered prolonged waterlogging, heavy salinity, and the loss of greenery, leaving the land barren. But with the support of SAJIDA Foundation’s ENGAGE4Sundarbans initiative, Jayanti is rebuilding what was lost and creating something greener and more resilient.

Jayanti Rani Saha’s story is a reminder that resilience is about thriving in harmony with the world around us. Her passion, resourcefulness, and commitment to sustainability inspire not only her community but also anyone who dreams of making a difference, no matter how small their resources may seem.

Jayanti Rani Saha is member of a female farmer group under the ENGAGE4Sundarbans Project.