Of Fish and Futures: A Grand Beginning through Re/lease

Blog by Spriha Roy, IIT Kharagpur. Spriha.roy24@gmail.com

On the 31st of August and the 5th of September 2025, the Mukherjee Canal in Kumirmari, an island situated in Gosaba block of the Indian Sundarbans, came alive with a vibrant community activity that focussed on ecological renewal. Spearheaded by the Sarsa Group—a collective comprising 41 households residing along the canal, the activity signified a milestone in the ongoing Collectivised Canal Fishing Experimentation (CCFE) initiative under the ENGAGE4Sundarbans project.

This two-phase release of fish fingerlings, conducted under the guidance of a transdisciplinary Indian team comprising academic researchers, local field implementation partners, advisory committee members, and technical experts from the Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFRI), brought together diverse forms of knowledge—scientific, traditional, and shared. As the fingerlings were gently introduced into the canal, the act of re/leasing became both a material and a symbolic gesture: of reinhabiting ecologies, of reimagining collective futures, and of reaffirming community-led management over shared aquatic commons.

This photo essay attempts to document not only the technical interventions in collectivised inland fishing, but also tries to highlight the deeply embodied place-based nuances of inter-generational knowledge systems, sustainable practices and hope. The images capture the multi-sensory textures of the occasion: the muddy feet and monsoon skies, the choreography of coordinated human chain carrying the boxes to the rhythms of dhak and conch shells, and systematically releasing the fingerlings to the canal.

Behind the Scenes of Planning and Logistics

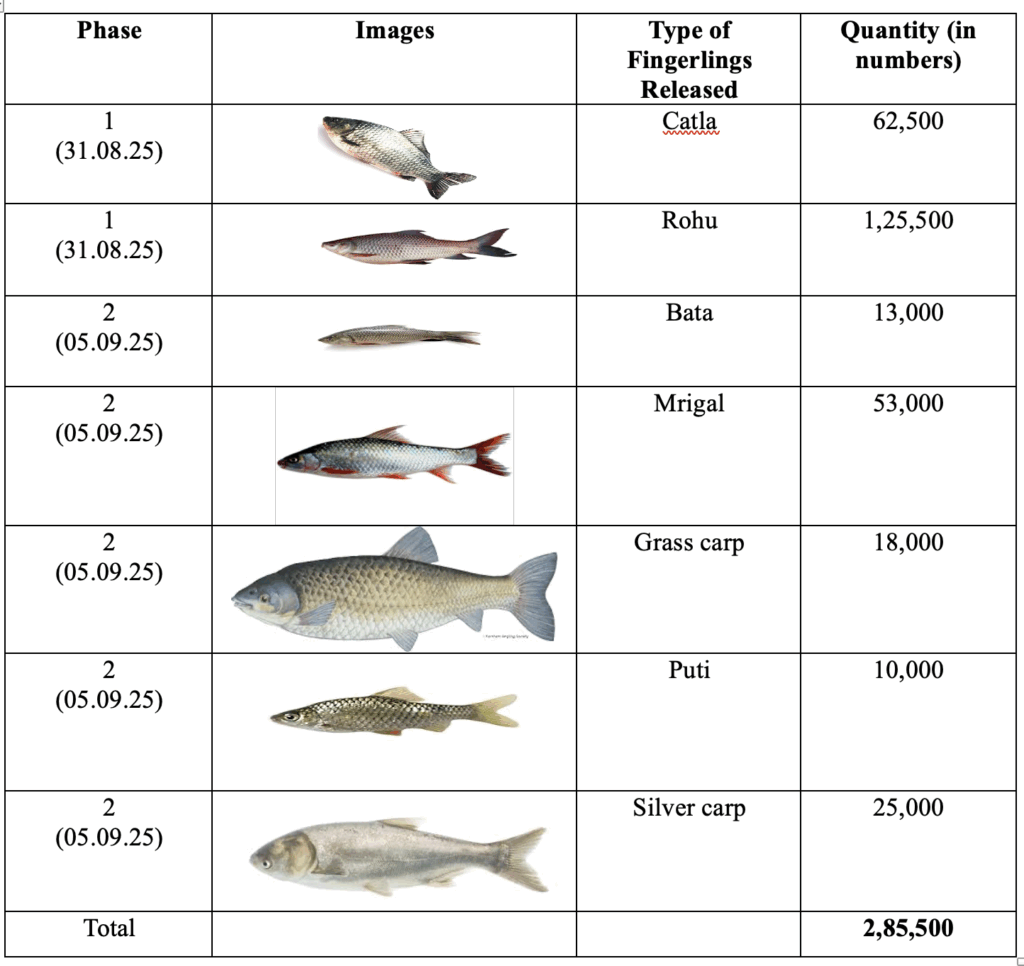

The fingerling release was preceded by intensive planning involving the project team, local community members, and technical experts. Multiple consultations were held to determine ecologically appropriate methods for releasing during both phases of the activity. Fingerlings were procured from a certified vendor in Naihati, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, and was transported in oxygenated plastic bags. The consignment included approximately 285,500 fingerlings distributed across seven species:

Each fingerling measured between 0.75-0.90 inches and weighed about 0.3 grams. The operation was coordinated under the supervision of a CIFRI principal scientist, in collaboration with the IIT Kharagpur team. After reaching Dhamakhali, the consignment was transferred to a boat and transported to Sucharita Sangha Ghat (Bonbibi Tala) in Kumirmari, the nearest access point to the Mukherjee Canal.

Image 1. Boat loaded with boxes of fingerlings brought to Sucharita Sangha Ghat in Kumirmari.

Image 2. Sarsa members welcoming the boat with great enthusiasm!

Rituals of Invocation

As the consignment of fingerlings reached Sucharita Sangha Ghat, the community gathered to celebrate this moment with traditional ritual of Makal and Ganga puja. Accompanied by the rhythmic beat of dhaks (traditional drums) and echoing vibrations of ullu and conch shells, members of the Sarsa Group offered prayers to invoke the blessings of the river. This act of reverence emphasises the culturally embedded symbolism of water in the community—as both a life-sustaining presence and a sacred force. Such traditional interventions serve as a medium between the perceived scientific practice and the unseen beliefs.

Image 3. Community members performing traditional rituals before the fish release.

Image 4. A member of the Sarsa group performing Ganga Puja.

Image 5. A collective comprising intergenerational participation and a commitment to sustaining the canal as a community-managed resource.

Collective Mobilisation through Human Chain

Following the offering rituals, community members formed a human chain to transport oxygenated boxes of fingerlings from the ghat to the canal’s edge. Navigating muddy terrain and narrow paths, this coordinated effort reflected both logistical precision and a shared sense of responsibility. The act of carrying became more than a practical task as it reflected collective effort in sustaining their canal ecosystem.

Image 6. Members of the Sarsa group carrying fingerling boxes from the ghat to the canal through a coordinated human chain.

Image 7. The members are walking across the Mukherjee canal with the boxes.

Image 8. Stacking the boxes at the end of the canal before the release.

Fingerlings Releasing Protocol

The release process followed standardised acclimatisation protocols to minimise stress and improve post-release survival. As per guidance from Dr. Archan Kumar Das, Principal Scientist at CIFRI, the oxygenated plastic bags, also referred to as fingerling balloons—were placed on the surface of the canal water, allowing them to float for approximately 15 minutes to achieve thermal equilibrium.

To further reduce stress on the sensitive fingerlings, about 100 ml of canal water (roughly one mug) was carefully added to each bag to initiate gradual acclimatisation. Once the fingerlings exhibited active movement, they were gently released at the canal’s edge, minimising shock and dispersal stress. This carefully managed process reflects a synthesis of technical precision and ecological care, integral to the broader aims of the Collectivised Canal Fishing Experimentation (CCFE).

Image 9. Floating fingerling balloons.

Image 10. Gradually adding 100ml canal water to each of the fingerling balloon.

Image 11. Releasing fish fingerlings in the canal.

More than the Re/lease: Reflections on Practice, People and Place

While the activity unfolded and began to gather momentum, an elderly man stood at a distance, observing the process attentively. When approached, he shared, “Though I am not a member of this collective, I am aware of the community initiative taking place, and I feel happy for my neighbours. My son works as a migrant labourer, and I run a small shop near the ghat. My earnings are sufficient, and I am able to manage. But this activity will help others to find ways for living.” His words mirrored not only a sense of solidarity, but also an acute awareness of the broader socio-economic impact this experiment promises to offer.

Among the Sarsa team members, one elderly participant stood out for his remarkable energy and commitment. Despite his age, he actively assisted in unwrapping the boxes with a level of stamina comparable to that of younger volunteers. When asked about his age, he responded, “I am 70 years old, and the first house in this lane belongs to me. Since my son is currently away for work, I am here to take his place. I may not be equipped to carry out the more complex procedures, but I can certainly help with unboxing the cardboard packages.” Such reflections are deeply meaningful in understanding the fundamental idea that no contribution is insignificant. His involvement, though modest in scope, played a vital role in supporting the overall coordination and success of fingerlings release event, highlighting the importance of inclusive community participation across generations.